The Oldest Promise

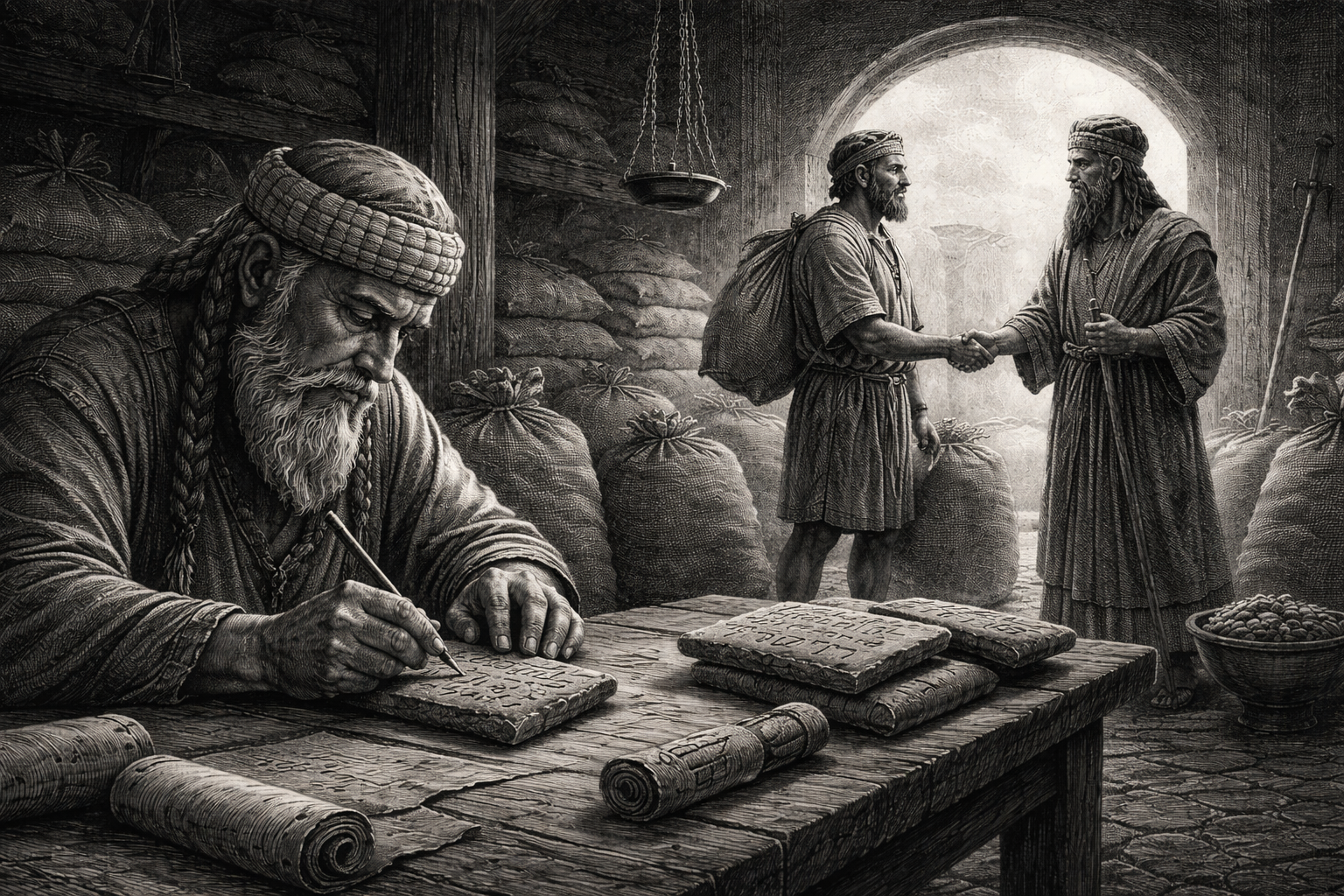

In a museum in Istanbul, there's a clay tablet about the size of your palm. It's 4,400 years old. The writing on it is cuneiform — wedge-shaped marks pressed into wet clay with a reed stylus, then baked hard in the Mesopotamian sun.

The tablet is a receipt for grain.

A farmer named Alulu (or something close to it — the scholars argue about the translation) delivered a quantity of barley to a temple storehouse. A scribe recorded the amount, the date, and both parties' marks. That was it. Transaction complete. Promise documented.

Forty-four centuries later, we know it happened. We know because they wrote it down.

Before Money, There Were Promises

The contract is older than money. This fact still astonishes me when I think about it clearly.

Before coins existed, before paper currency, before anyone had conceived of a bank or a stock market, humans had already figured out the contract. They had already solved the fundamental problem of civilization: how do you make agreements that outlast the moment?

The Sumerians didn't invent the contract because they were litigious. They invented it because they were practical. Grain needed to be stored between harvests. Sheep needed to be lent for breeding. Land needed to be transferred between generations. Without writing, all of this depended on memory — and memory, as every human learns eventually, cannot be trusted.

So they made marks on clay. Simple marks, witnessing simple promises. I will deliver this. You will pay that. Here is the proof that we agreed.

The contract made civilization possible. Not philosophy, not art, not religion — those came later, built on the foundation of people being able to make and keep agreements. The contract was the technology that allowed strangers to cooperate, that let complexity emerge from chaos, that gave humans a way to trust each other across time.

The Evolution of Promise

Every civilization that achieved anything discovered the contract independently.

The Egyptians had hieratic contracts — written in the shorthand of scribes, recording land sales and marriages and debts. The Chinese had their own systems dating back to the Shang dynasty, oracle bones recording obligations between nobles and gods. The Romans, as they did with everything, systematized it — stipulatio, contractus, the foundations of the legal tradition that still shapes half the world.

The content changed. The form varied. But the core remained constant: two parties, an agreement, and documentation.

My grandfather — a fisherman who never traveled more than fifty miles from the island where he was born — understood this instinctively. When he sold his catch to the merchant in the harbor, there was a ledger. The merchant wrote down what he bought, what he paid, what he owed. My grandfather made his mark. Neither could read the other's language well, but they could read numbers, and they could point to the ledger when disagreements arose.

"The book doesn't lie," my grandfather used to say. "Men lie. The book remembers."

He was practicing the same art as those Sumerian scribes, separated by four thousand years and ten thousand miles. The technology changed — clay to papyrus to paper to whatever we use now — but the principle never did.

What We Lost

Somewhere in the twentieth century, something went wrong.

The contract — this elegant, ancient invention — became a weapon. It became a maze. It became a document that required specialized training to read, that took hours to navigate, that intimidated ordinary people into signing things they didn't understand.

I don't know exactly when it happened. Maybe it was the rise of corporations, entities that needed armies of lawyers to speak on their behalf. Maybe it was the growth of liability law, the fear of lawsuits that drove every agreement toward defensive complexity. Maybe it was simply the accumulation of edge cases, each one adding another clause until the simple promise disappeared beneath layers of contingency.

Whatever the cause, the result is clear. The contract became something to dread rather than something to rely on.

My nephew tells me stories. A client who wanted to hire him for a simple renovation — three weeks of work, straightforward terms. The client's company required their "standard contractor agreement." Forty-seven pages. Clauses about intellectual property (for a bathroom renovation). Clauses about non-disparagement. Clauses about indemnification that seemed to make my nephew responsible for acts of God.

He read it three times and still didn't fully understand what he was agreeing to. He signed it anyway, because what choice did he have? The client wasn't willing to negotiate, and he needed the work.

This is what we've done to the oldest promise. We've turned it into something that requires surrender rather than agreement.

The Temple and the Tower

There's a parallel that haunts me.

The Sumerians built temples — ziggurats, they called them, great stepped towers rising above the flat plains of Mesopotamia. These temples were meant to bring humans closer to the gods. They were expressions of faith, of aspiration, of humanity reaching upward.

Over time, the temples became institutions. Priests became bureaucrats. What started as a simple act of devotion became entangled with taxation, with land management, with politics. The ziggurats remained, but their meaning changed. They became symbols of power rather than pathways to the divine.

I think about this when I look at modern contracts. The simple act of promise-making — two people agreeing to something and writing it down — has become entangled with legal departments, compliance requirements, enterprise software. What should take minutes takes hours. What should cost nothing costs hundreds of dollars a month.

We built towers on top of the simple act, and now we can barely see the foundation.

The Way Back

Here is what gives me hope: the foundation is still there.

Beneath all the complexity, the contract is still what it always was. Two parties. An agreement. Documentation. Everything else is ornamentation.

And ornamentation can be stripped away.

I've watched technology do this in other areas. Photography used to require specialists with expensive equipment and chemical expertise. Now anyone with a phone can take a picture. Publishing used to require printing presses and distribution networks. Now anyone with an internet connection can share their writing with the world.

The tools got simpler. The act became accessible. The essence was preserved while the barriers fell.

I believe the same thing can happen with contracts. Not by making them less binding or less meaningful, but by making them less burdensome. By returning to what the Sumerians understood: the point is the promise, not the process.

Twenty-five cents to send a contract. No legal department required. No forty-seven-page templates. Just: here's what we're agreeing to, here's where you sign, here's your copy.

That's not a reduction of the contract. That's a restoration. That's taking five thousand years of human invention and clearing away the accumulated debris so the original purpose can shine through.

Alulu's Barley

I think about Alulu sometimes, the farmer whose grain receipt survives in that Istanbul museum.

He had no lawyers. No enterprise software. No monthly subscription to a signing platform. He had an agreement to deliver barley, a scribe to document it, and a piece of clay to make it permanent.

Forty-four centuries later, we know he kept his promise. The record survived wars and empires and the rise and fall of civilizations. The simplest technology — marks in clay — outlasted everything that came after.

There's a lesson in that. The simple things endure. The complicated things collapse under their own weight.

The contract doesn't need to be reinvented. It needs to be remembered. It needs to be what it was before we buried it under our anxieties and our bureaucracies and our enterprise pricing tiers.

A promise, written down, between people who mean it.

That's the oldest technology we have. That's the foundation everything else is built on.

We should treat it with more respect.

The supply boat brought me a book last month — a history of writing systems, three hundred pages of scholarship on how humans learned to make marks that meant things. I'm halfway through. The chapter on Sumerian contracts is dog-eared.

Outside, the ice is shifting. I can hear it groaning in the dark, the sound of something ancient and patient rearranging itself. The light turns above me, the same signal that's been burning here for over a century.

Some things don't need to change. Some things were right the first time.

Gilberto Mares has been keeper of the Kråkeholm Light for fifty years. He writes about time, tools, and the things that matter. He does not have a smartphone.