The Weight of a Signature

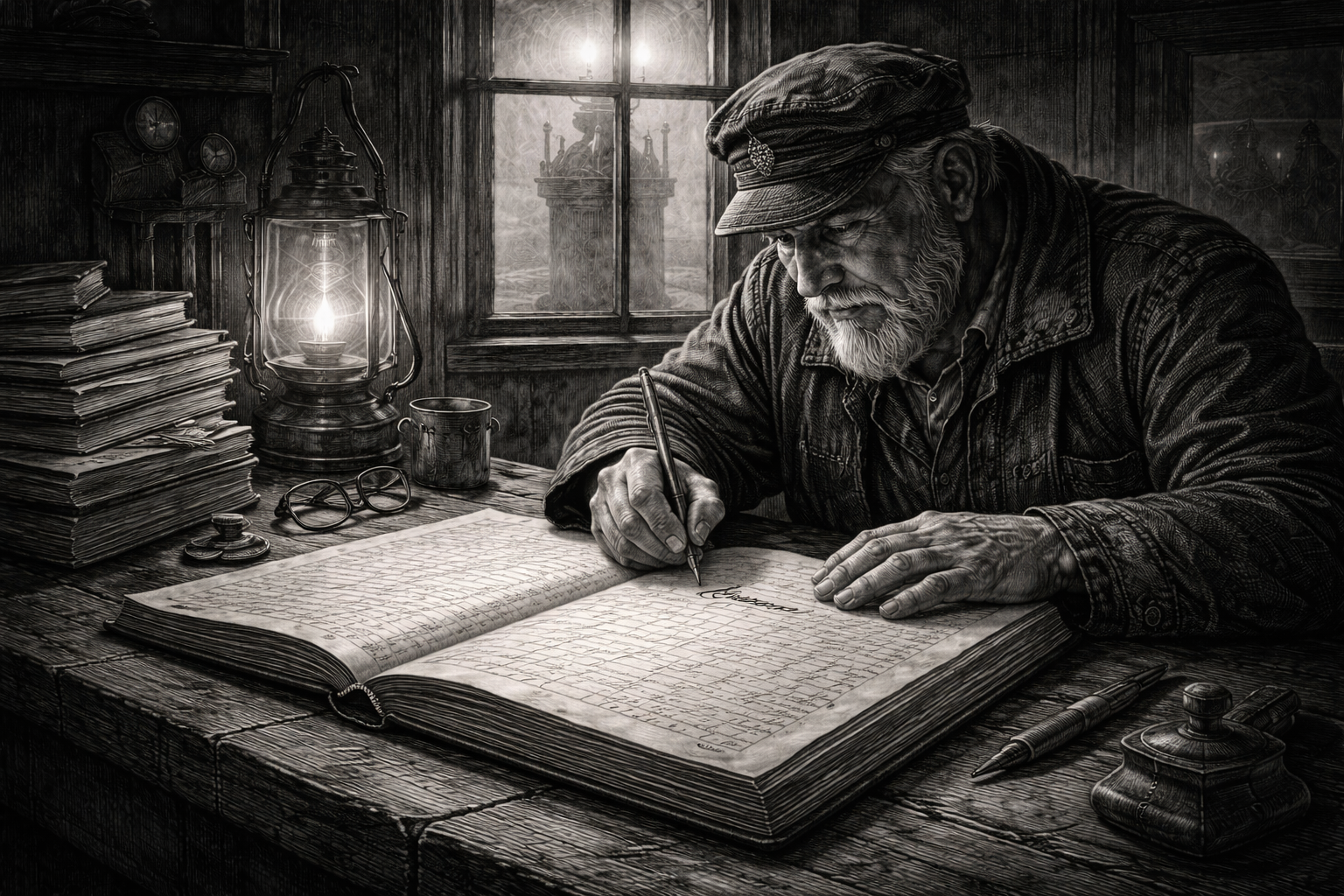

I've signed my name 18,262 times in this lighthouse.

I know the exact number because I've kept the logbook since 1975. Every day, without exception, I record the weather, the visibility, any ships that passed, any maintenance performed. And at the bottom of each entry, I sign my name. Gilberto Mares. The same name, in the same hand, for fifty years.

The early signatures look different. The handwriting of a young man — hurried, a little careless, the letters not quite settled into themselves. If you flip through the decades, you can watch my signature age. It slows down somewhere in the eighties. Gets more deliberate in the nineties. By now, it's the signature of an old man who has learned that there's no reason to rush.

Every one of those signatures was a small promise. I was here. I did my job. The light stayed on.

What a Signature Used to Mean

The Sumerians were signing documents five thousand years ago. Not with names as we know them, but with cylinder seals — small carved stones they would roll across wet clay to leave an impression. Your seal was your identity. It was how you said, "I agree to this. I stand behind it. Hold me to it."

The Egyptians signed with cartouches. The Romans developed a system of subscriptio — literally writing your name below a document to indicate consent. In medieval Europe, most people couldn't write, so they made marks. An X, witnessed by someone who could record whose X it was.

For most of human history, signing something was an event. It meant something. You didn't sign casually, because your name carried weight. A signature was a piece of yourself you left behind, attached to a promise that would outlive the moment.

Sailors understood this. When a captain signed the ship's manifest, he was accepting responsibility for every soul aboard. When a sailor signed articles, he was binding himself to a voyage that might last years, that might end in death. They didn't have lawyers redlining terms. They had a document, a pen, and the understanding that your name meant your word.

The Inflation of Signatures

Somewhere along the way, we broke this.

I read once that the average person in a developed country signs their name over 50,000 times in a lifetime. Terms of service. Credit card receipts. Package deliveries. Forms at the doctor's office. Consent agreements for software you'll use once and forget.

We sign so often that we've forgotten what it means. The signature has been inflated into worthlessness, like a currency printed without limit. When you sign everything, you sign nothing.

I watch this happen even here, at the edge of the world. The supply boat captain has me sign for deliveries now — a new regulation from some office in Copenhagen. I sign for boxes of canned goods and diesel fuel, my name on a form that will be filed somewhere and never read. It feels like a small theft each time. Not of money, but of meaning.

The signature used to be a moment of commitment. Now it's just a speed bump on the way to whatever comes next.

The Logbook and the Lie

There's a story I think about often.

In 1911, a lighthouse keeper in Nova Scotia falsified his log. He'd been drunk for three days, the light had gone out, and a fishing boat had run aground on the rocks. Two men drowned. When the inspectors came, he showed them the logbook with its tidy entries and his signature at the bottom of each page. Everything in order.

They caught him, of course. The dates on the oil deliveries didn't match his recorded usage. His signature had become a lie, and the lie had cost lives.

I think about him when I sign my own log each night. The signature isn't just proof that I was here. It's a promise that what I've written is true. That's the weight of it. That's what we've forgotten.

When you sign something, you're not just moving a pen. You're saying: this is true, and I'll stand behind it. If you're not willing to stand behind it, you shouldn't sign it. And if the thing you're signing doesn't matter enough to stand behind — why are you signing it at all?

The Case for Less

I don't think we need to sign less often. I think we need to sign less thoughtlessly.

A contract between two parties who genuinely need to formalize an agreement — that signature matters. It should feel like something. Both people should pause, even for a moment, and recognize that they're making a commitment.

But that moment gets lost when the signing process takes an hour. When you have to create an account, verify an email, click through pages of instructions, and navigate a system designed for legal departments with full-time administrators. By the time you actually sign, you're not thinking about the commitment. You're thinking about all the time you just lost.

This is what I appreciate about simple tools. They get out of the way. They let the signature be what it was always supposed to be — a moment of agreement, not an ordeal of administration.

My Father's Signature

My father was a fisherman in the Azores before he was anything else. He signed his name on exactly three documents in his life: his marriage certificate, the deed to his house, and the papers that sent me to school on the mainland.

He talked about each of those signatures until the day he died. The marriage certificate, he signed with a trembling hand because he wasn't sure he deserved my mother. The deed, he signed with pride because it meant he owned something permanent in a life that had been built on the shifting sea. The school papers, he signed with sadness because he knew it meant I would leave and probably not come back.

Three signatures. Each one a turning point. Each one remembered for sixty years.

I wonder what he would make of a world where people sign their names fifty thousand times and remember none of them. I think he would find it very sad. I think he would say we had taken something sacred and made it ordinary.

The Light at the End

Here is what I know, after fifty years of signing my name at the bottom of a logbook:

A signature should cost you something. Not money — attention. The few seconds it takes to recognize that you're making a promise. The awareness that your name will be attached to this document long after the moment has passed.

If the process of signing has become so burdensome that you just want it over with, the process is broken. If you're signing things so often that each signature blurs into the next, something has gone wrong.

The tools we use for signatures should make the act easier, not the commitment cheaper. They should remove the friction of the process so that the weight of the signature can be felt again.

Twenty-five cents to send a contract. No accounts to create, no systems to navigate, no hour lost to administration. Just the document, the signature line, and the moment of commitment that humans have recognized for five thousand years.

That's all it should be. That's all it ever was.

Tonight I will sign my logbook for the 18,263rd time. The weather is clear, the visibility unlimited, and no ships have passed. The light is on. My name is at the bottom of the page. It still means something to me. I hope it always will.

Gilberto Mares has been keeper of the Kråkeholm Light for fifty years. He writes about time, tools, and the things that matter. He does not have a smartphone.