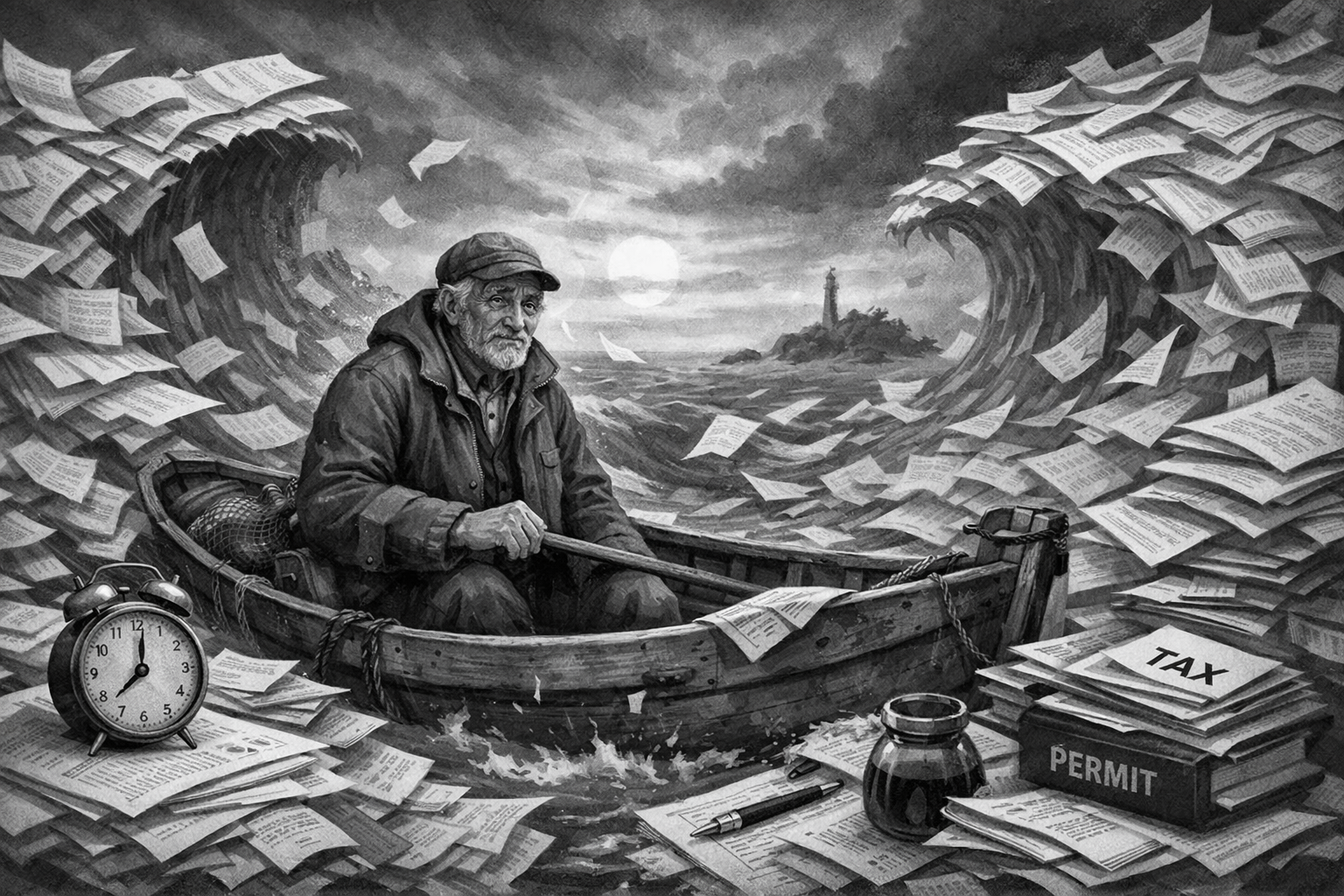

Time and the Paperwork Sea

Let me tell you about a man named Einar.

Einar was a fisherman who worked these waters for forty years. Not an exceptional fisherman — not the biggest catches, not the most daring voyages — just a solid, reliable man who went out, did his work, and came home. The kind of person who holds a community together without anyone noticing.

When Einar retired, he did something unusual. He went back through his logbooks, his receipts, his records — all the paperwork he'd accumulated over four decades — and he tried to calculate how much time he'd spent on administration. Not fishing. Not maintaining his boat. Not selling his catch or negotiating with buyers. Just paperwork. Forms, reports, compliance documents, tax filings, licensing renewals.

The number he came up with was 14,600 hours.

Two years. Not work hours — two full years of twenty-four-hour days. If you count only waking hours, it was closer to three years. Three years of a forty-year career spent filling out forms, waiting on hold, and navigating bureaucracies that added nothing to the fish he caught or the family he fed.

Einar told me this over coffee, two years before he died. He wasn't bitter about it — that wasn't his way — but he was bewildered. "I keep trying to figure out what it was for," he said. "All those hours. What did they produce? What do they have to show for taking them from me?"

I didn't have an answer. I still don't.

The Sea That Rises

Paperwork is like water. It will fill whatever space you give it.

I've watched this happen over fifty years. When I arrived at Kråkeholm in 1975, my administrative duties were minimal. A logbook entry each day. A monthly report to the maritime authority. An annual inspection. Perhaps ten hours a month, total.

Now? The logbook remains, but it's been joined by environmental compliance reports, equipment certification renewals, safety documentation, digital reporting systems that duplicate the paper ones, and forms I don't understand from agencies I've never heard of.

The light hasn't changed. The job hasn't changed. The rocks are in the same place; the ships still need guidance. But the paperwork has grown every year, like ice advancing across the sea.

And I'm a lighthouse keeper. I have one of the simplest jobs in the world. Imagine what it's like for people running actual businesses.

The Invisible Drowning

The cruelest thing about paperwork is that it kills you slowly.

No one wakes up and decides to spend three years of their life on forms. It happens five minutes at a time. A quick form here. A short report there. A signature needed before lunch. A renewal that won't take long.

Each individual task seems trivial. What's five minutes? What's an hour? You have plenty of time.

But time doesn't work that way. Time is finite. Every five minutes spent on a form that produces nothing is five minutes not spent on something that matters. Every hour lost to administrative friction is an hour that could have gone to your work, your family, your own quiet moments of peace.

The drowning is invisible because it happens in increments too small to notice. You don't feel the water rising. You just wake up one day, like Einar, and realize you've lost years to something you can barely remember.

The False Economy

The strangest part is that all this paperwork is supposed to make things more efficient.

That's the promise, isn't it? We need documentation for accountability. We need records for compliance. We need systems for tracking. The bureaucracy exists to make the underlying work run more smoothly.

But somewhere, the administration became the work. The tracking became more important than the thing being tracked. The documentation grew until it consumed more resources than the activity it documented.

I see this in my nephew's business. He spends more time managing contracts than executing them. More time on invoicing than on the work being invoiced. More time proving he's compliant than actually doing the things compliance is meant to ensure.

The overhead has become greater than the operation. The tail wags the dog.

And every hour spent on this overhead is extracted from somewhere. From the work itself. From the evenings with family. From the weekends that used to be free. From the sleep that gets cut short because there's one more form to finish.

The economy of paperwork is a false economy. It doesn't save time; it shifts the cost to people who can't refuse to pay.

What I've Learned From Stillness

I've lived in the same lighthouse for fifty years. I've had more silence than most people experience in a lifetime. And in that silence, I've had time to think about time.

Here's what I've concluded: we have far less of it than we pretend.

The average human lifespan is about 700,000 hours. That sounds like a lot until you realize a third of it is sleep. Another third is childhood, education, and the years when we're too old to do much. The part in the middle — the part where we're healthy, capable, and free to choose how we spend our days — is maybe 200,000 hours.

That's it. That's your whole adult life, measured in hours.

And of those 200,000 hours, how many are lost to paperwork? To administrative systems that serve no one's interest? To forms designed by people who will never have to fill them out?

Einar lost 14,600 hours. That's 7% of his entire adult life, gone to forms. And he was a fisherman — someone doing relatively simple work with relatively simple paperwork.

For people in more regulated industries, the number is higher. For people running businesses, it's higher still. I've heard estimates that small business owners spend 20% of their working time on administration.

One day in five, lost to the paperwork sea.

The Unnecessary Weight

Not all paperwork is unnecessary. Some documentation genuinely matters. Contracts that protect both parties. Records that enable accountability. Reports that inform real decisions.

But so much of it is unnecessary. Forms required because they've always been required. Reports no one reads. Signatures demanded for their own sake, not because they add value.

I think about the signature pads at grocery stores. Sign here to confirm you're buying milk and bread. What purpose does that serve? What fraud is being prevented? What accountability is being created?

None. It's theater. Administrative theater performed millions of times a day, each performance stealing thirty seconds from someone's life.

Thirty seconds doesn't sound like much. But there are 330 million people in America. If each of them signs a pointless signature pad once a week, that's 275,000 hours per week. 14 million hours per year. The equivalent of 1,600 human lifetimes, spent confirming grocery purchases.

This is what we've built. A world where the machinery of administration consumes more life than the activities it administers.

The Way Out

I'm not naive enough to think we can eliminate paperwork. Some of it is necessary. Some of it, despite appearances, actually serves a purpose.

But we can refuse to participate in the unnecessary parts. We can choose tools that minimize rather than maximize administrative burden. We can push back against systems designed without regard for the time they steal.

When I recommend simple tools to people — simple contracts, simple processes, simple systems — I'm not just recommending convenience. I'm recommending the reclamation of time.

Twenty-five cents to send a contract. A few minutes to complete the process. No accounts to create, no systems to learn, no hours lost to setup and configuration.

That's not just a pricing model. That's a philosophy. The tool should serve you, not the other way around.

Every minute a good tool saves you is a minute returned to your life. A minute you can spend on work that matters, or on rest that's deserved, or on the people you love. A minute that's yours again, rescued from the paperwork sea.

Einar's Last Fishing Trip

The last time I saw Einar, he was preparing for what he knew would be his final voyage. Not a commercial trip — just an old man taking his boat out one more time, because the sea had been his life and he wanted to say goodbye.

He didn't file any forms. He didn't notify any authorities. He just untied the lines and motored out past the rocks, into the gray water, where the horizon swallowed him for a few hours.

When he came back, he was smiling. "No paperwork," he said. "Just the sea. Like it used to be."

He died six weeks later. But that last trip — those few hours of pure, unmediated experience — mattered to him more than I can express. He talked about it constantly in his final days. The freedom of it. The simplicity.

That's what we're fighting for when we fight against unnecessary administration. Not efficiency. Not productivity. Freedom. The freedom to spend your hours on things that matter, with people who matter, doing work that means something.

The paperwork sea will always be there. The forms will always multiply. But we can choose to swim, and we can choose tools that help us keep our heads above water.

Time is the only thing we can't earn back. Every hour matters. Every minute counts.

Don't let the sea take more than it has to.

It's 4 AM. The coffee is hot. The light is turning above me, the same rotation it's made every night for a century. Outside, the ice groans and shifts in the darkness.

I have a few hours before dawn. No forms to fill out. No reports due. Just the quiet, the coffee, and these words.

This is what freedom feels like. I wish it for everyone.

Gilberto Mares has been keeper of the Kråkeholm Light for fifty years. He writes about time, tools, and the things that matter. He does not have a smartphone.